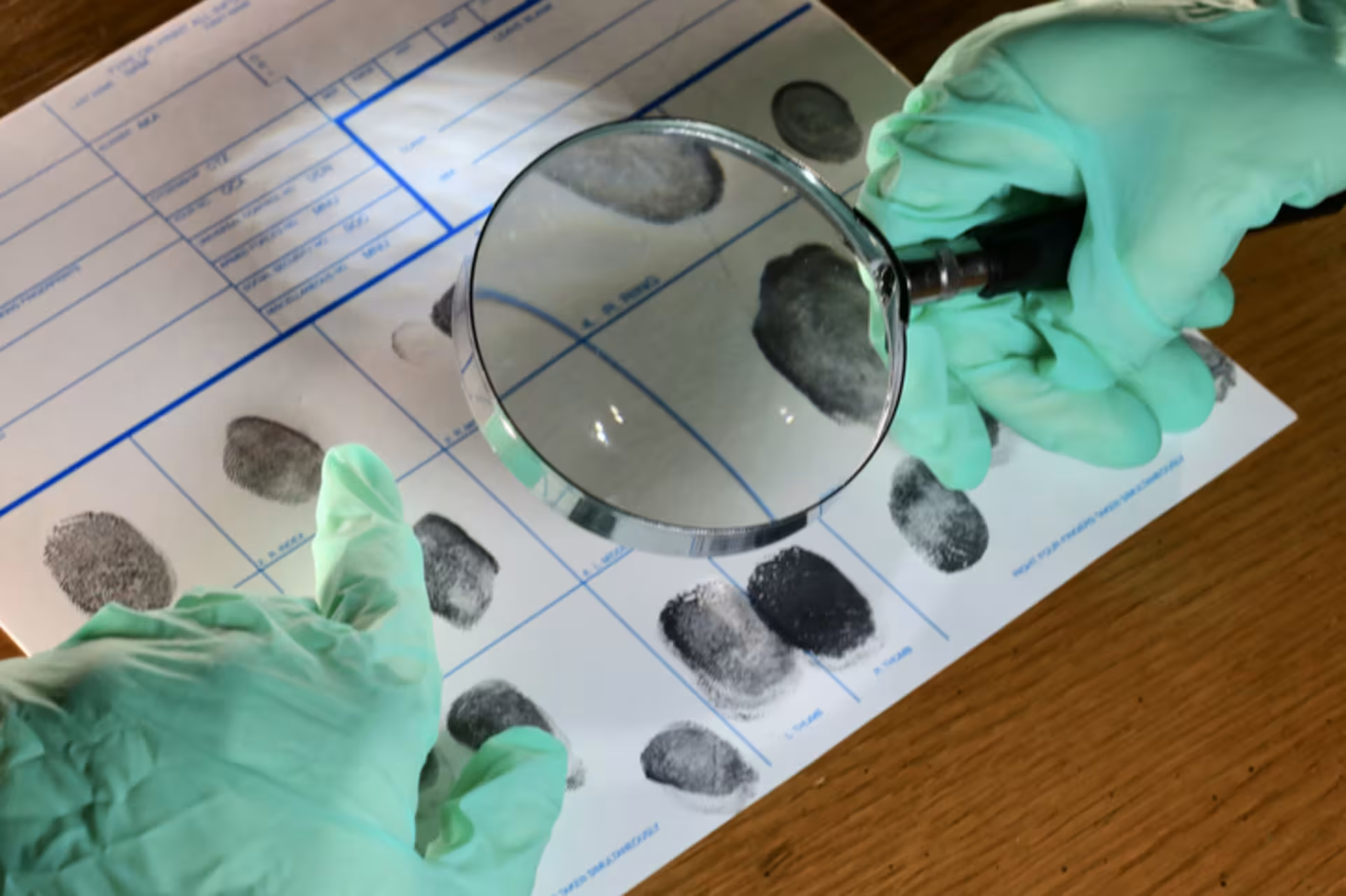

Criminal Justice, Government, and Public Administration

About the Minds and Numbers Blog

Presented by College of Humanities and Social Sciences

As the title of our blog suggests, these posts by College of Humanities and Social Sciences (CHSS) faculty and special guests will engage, inform and challenge you in a myriad of ways. The posts reflect the diversity of our programs of study: degrees that are traditional (history), current (justice studies and communications), academic (English literature) and career-oriented (psychology, counseling, criminal justice and government). Here, there is something for everyone.